The Tulsa Race Massacre is just one of the starkest examples of how Black wealth has been sapped, again and again, by racism and racist violence — forcing generation after generation to start from scratch while shouldering the burdens of being Black in America.

TULSA, Okla. — On a recent Sunday, Ernestine Alpha Gibbs returned to Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Not her body. She had left this Earth 18 years ago, at age 100. But on this day, three generations of her family brought Ernestine’s keepsakes back to this place which meant so much to her. A place that was, like their matriarch, a survivor of a long-ago atrocity.

Albums containing black-and-white photos of the grocery business that has employed generations of Gibbses. VHS cassette tapes of Ernestine reflecting on her life. Ernestine’s high school and college diplomas, displayed in not-so-well-aged leather covers.

The diplomas were a point of pride. After her community was leveled by white rioters in 1921 — after the gunfire, the arson, the pillaging — the high school sophomore temporarily fled Tulsa with her family. “I thought I would never, ever, ever come back,” she said in a 1994 home video.

But she did, and somehow found a happy ending.

“Even though the riot took away a lot, we still graduated,” she said, a smile spreading across her face. “So, we must have stayed here and we must have done all right after that.”

Not that the Gibbs family had it easy. And not that Black Tulsa ever really recovered from the devastation that took place 100 years ago, when nearly every structure in Greenwood, the fabled Black Wall Street, was flattened — aside from Vernon AME.

The Tulsa Race Massacre is just one of the starkest examples of how Black wealth has been sapped, again and again, by racism and racist violence — forcing generation after generation to start from scratch while shouldering the burdens of being Black in America.

All in the shadow of a Black paradise lost.

“Greenwood proved that if you had assets, you could accumulate wealth,” said Jim Goodwin, publisher of the Oklahoma Eagle, the local Black newspaper established in Tulsa a year after the massacre.

“It was not a matter of intelligence, that the Black man was inferior to white men. It disproved the whole idea that racial superiority was a fact of life.”

___

Prior to the massacre, only a couple of generations removed from slavery, unfettered Black prosperity in America was urban legend. But Tulsa’s Greenwood district was far from a myth.

Many Black residents took jobs working for families on the white side of Tulsa, and some lived in detached servant quarters on weekdays. Others were shoeshine boys, chauffeurs, doormen, bellhops or maids at high-rise hotels, banks and office towers in downtown Tulsa, where white men who amassed wealth in the oil industry were kings.

But down on Black Wall Street — derided by whites as “Little Africa” or “N——-town” — Black workers spent their earnings in a bustling, booming city within a city. Black-owned grocery stores, soda fountains, cafés, barbershops, a movie theater, music venues, cigar and billiard parlors, tailors and dry cleaners, rooming houses and rental properties: Greenwood had it.

According to a 2001 report of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the Greenwood district also had 15 doctors, a chiropractor, two dentists, three lawyers, a library, two schools, a hospital, and two Black publishers printing newspapers for north Tulsans.

Tensions between Tulsa’s Black and white populations inflamed when, on May 31, 1921, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune published a sensationalized report describing an alleged assault on Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white girl working as an elevator operator, by Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoeshine.

“Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” read the Tribune’s headline. The paper’s editor, Richard Lloyd Jones, had previously run a story extolling the Ku Klux Klan for hewing to the principle of “supremacy of the white race in social, political and governmental affairs of the nation.”

Rowland was arrested. A white mob gathered outside of the jail. Word that some in the mob intended to kidnap and lynch Rowland made it to Greenwood, where two dozen Black men had armed themselves and arrived at the jail to aid the sheriff in protecting the prisoner.

Their offer was rebuffed and they were sent away. But following a separate deadly clash between the lynch mob and the Greenwood men, white Tulsans took the sight of angry, armed Black men as evidence of an imminent Black uprising.

There were those who said that what followed was not as spontaneous as it seemed — that the mob intended to drive Black people out of the city entirely, or at least to drive them further away from the city’s white enclaves.

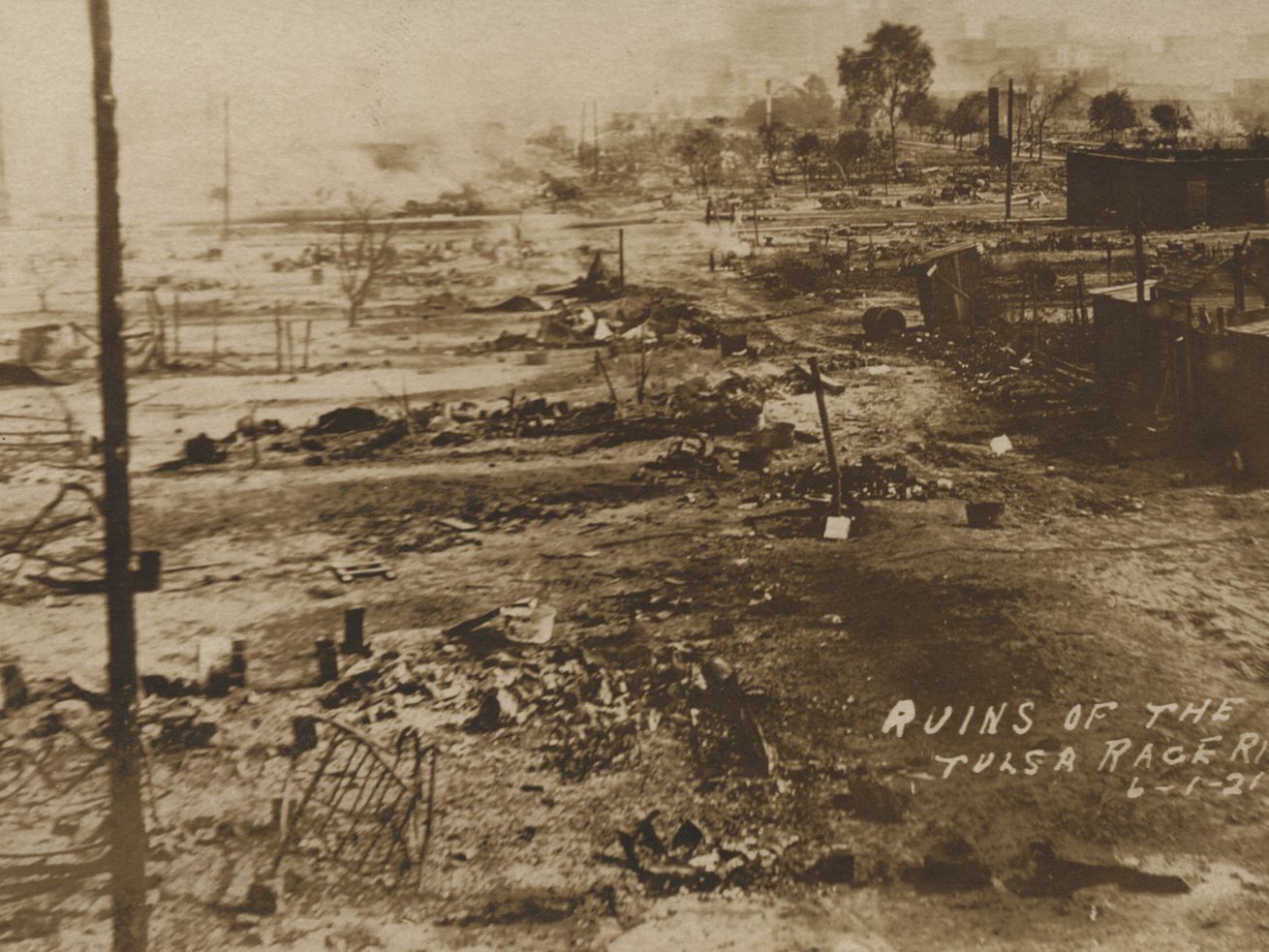

Over 18 hours, between May 31 and June 1, whites vastly outnumbering the Black militia carried out a scorched-earth campaign against Greenwood. Some witnesses claimed they saw and heard airplanes overhead firebombing and shooting at businesses, homes and people in the Black district.

More than 35 city blocks were leveled, an estimated 191 businesses were destroyed, and roughly 10,000 Black residents were displaced from the neighborhood where they’d lived, learned, played, worked and prospered.

Although the state declared the massacre death toll to be only 36 people, most historians and experts who have studied the event estimate the death toll to be between 75 and 300. Victims were buried in unmarked graves that, to this day, are being sought for proper burial.

The toll on the Black middle class and Black merchants is clear. According to massacre survivor Mary Jones Parrish’s 1922 book, R. T. Bridgewater, a Black doctor, returned to his home to find his high-end furniture piled in the street.

“My safe had been broken open, all of the money stolen,” Bridgewater said. “I lost 17 houses that paid me an average of over $425 per month.”

Tulsa Star publisher Andrew J. Smitherman lost everything, except for the metal printing presses that didn’t melt in the fires at his newspaper’s offices. Today, some of his descendants wonder what could have been, if the mob had never destroyed the Smitherman family business.

“We’d be like the Murdochs or the Johnson family, you know, Bob Johnson who had BET,” said Raven Majia Williams, a descendant of Smitherman’s, who is writing a book about his influence on Black Democratic politics of his time.

“My great-grandfather was in a perfect position to become a media mogul,” Williams said. “Black businesses were able to exist because they could advertise in his newspaper.”

Smitherman moved on to Buffalo, New York, where he opened another newspaper. It was a struggle; eventually, after his death in 1961, the Empire Star went under.

“It wasn’t a very large office, so I’d often see the bills,” said his grandson, William Dozier, who worked there as a boy. “Many of them were marked past due. We didn’t make a lot of money. He wasn’t able to pass any money down to his daughters, although he loved them dearly.”

___

After the fires in Greenwood were extinguished, the bodies buried in unmarked mass graves, and the survivors scattered, insurance companies denied most Black victims’ loss claims totaling an estimated $1.8 million. That’s $27.3 million in today’s currency.

Over the years, the effects of the massacre took different shapes. Rebuilding in Greenwood began as soon as 1922 and continued through 1925, briefly bringing back some of Black Wall Street.

Then, urban renewal in the 1950s forced many Black businesses to relocate further into north Tulsa. Next came racial desegregation that allowed Black customers to shop for goods and services beyond the Black community, financially harming the existing Black-owned business base. That was followed by economic downturns, and the construction of a noisy highway that cuts right through the middle of historic Greenwood.

Chief Egunwale Amusan, president of the African Ancestral Society in Tulsa, regularly gives tours around what’s left. Greenwood was much more than what people hear in casual stories about it, he recently told a small tour group as they turned onto Greenwood Avenue in the direction of Archer Avenue.

Interstate 244 dissects the neighborhood like a Berlin wall. But it is easy for visitors to miss the engraved metal markers at their feet, indicating the location of a business destroyed in the massacre and whether it had ever reopened.

“H. Johnson Rooms, 314 North Greenwood, Destroyed 1921, Reopened,” reads one marker.

“I’ve read every book, every document, every court record that you can possibly think of that tells the story of what happened in 1921,” Amusan told the tour group in mid-April. “But none of them did real justice. This is sacred land, but it’s also a crime scene.”

No white person has ever been imprisoned for taking part in the massacre, and no Black survivor or descendant has been justly compensated for who and what they lost.

“What happened in Tulsa wasn’t just unique to Tulsa,” said the Rev. Robert Turner, the pastor of Vernon AME Church. “This happened all over the country. It was just that Tulsa was the largest. It damaged our community. And we haven’t rebounded since. I think it’s past time that justice be done to atone for that.”

Some Black-owned businesses operate today at Greenwood and Archer avenues. But it’s indeed a shadow of what has been described in books and seen in century-old photographs of Greenwood in its heyday.

A $30 million history center and museum, Greenwood Rising, will honor the legacy of Black Wall Street with exhibits depicting the district before and after the massacre, according to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission. But critics have said the museum falls far short of delivering justice or paying reparations to living survivors and their descendants.

Tulsa’s 1921 Black population of 10,000 grew to roughly 70,500 in 2019, according to a U.S. Census Bureau estimate; the median household income for Tulsa’s Black households was an estimated $30,955 in 2019, compared to $55,278 for white households. In a city of an estimated 401,760 people, close to a third of Tulsans living below the poverty line in 2019 were Black, while 12% were white.

The disparities are no coincidence, local elected leaders often acknowledge. The inequalities also show up in business ownership demographics and educational attainment.

Attempts to force Tulsa and the state of Oklahoma to take some accountability for their role in the massacre suffered a major blow in 2005, when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear survivors’ and victim descendants’ appeal of a lower federal court ruling. The courts had tossed out a civil lawsuit because, justices held, the plaintiffs had waited too long after the massacre to file it.

Now, a few living massacre survivors —106-year-old Lessie Benningfield Randle, 107-year-old Viola Fletcher, and 100-year-old Hughes Van Ellis — along with other victims’ descendants are suing for reparations. The defendants include the local chamber of commerce, the city development authority and the county sheriff’s department.

“Every time I think about the men and women that we’ve worked with, and knowing that they died without justice, it just crushes me,” said Damario Solomon-Simmons, a native Tulsan who is a lead attorney on the lawsuit and founder of the Justice for Greenwood Foundation.

“They all believed that once the conspiracy of silence was pierced, and the world found out about the destruction, the death, the looting, the raping, the maiming, (and) the wealth that was stolen … that they would get justice, that they would have gotten reparations.” Solomon-Simmons said.

The lawsuit, which is brought under Oklahoma’s public nuisance statute, seeks to establish a victims’ compensation fund paid for by the defendants. It also demands payment of outstanding insurance policy claims that date back to the massacre.

Republican Mayor G.T. Bynum, who is white (Tulsa has never had a Black mayor), does not support paying reparations to massacre survivors and victims’ descendants. Bynum said such a use of taxpayers’ money would be unfair to Tulsans today.

“You’d be financially punishing this generation of Tulsans for something that criminals did a hundred years ago,” Bynum said. “There are a lot of other areas of focus, when you talk about reparations. People talk about acknowledging the disparity that exists, and recognizing that there is work to do in addressing those disparities and making this city one of greater equality.”

State Sen. Kevin Matthews, who is Black and chairs the massacre centennial commission, said no discussion of reparations can happen without reconciliation and healing. He believes the Greenwood Rising history center, planned for his legislative district, is a start.

“We talked to people in the community,” Matthews said. “We wanted the story told first. So this is my first step, and I do agree that reparations should happen. Part of reparations is to repair the damage of even how the story was told.”

___

Among the treasured keepsakes that came home to Vernon AME was a certificate of recent vintage that recognized Ernestine Gibbs as a survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

But for Ernestine and her family, the real pride is not in survival. It is in surmounting disaster, and in carrying on a legacy of Black entrepreneurial spirit that their ancestors exemplified before and after the massacre.

After graduating from Langston University, Ernestine married LeRoy Gibbs. Even as she taught in the Tulsa school system for 40 years, Ernestine and her husband opened a poultry and fish market in the rebuilt Greenwood in the 1940s. They sold turkeys to order during the holidays.

Carolyn Roberts, Ernestine’s daughter, said although her parents lived with the trauma of the massacre, it never hindered their work ethic: “They survived the whole thing and bounced back.”

Urban renewal in the late 1950s forced LeRoy and Ernestine to move Gibbs Fish & Poultry Market further into north Tulsa. The family purchased a shopping center, expanded the grocery market and operated other businesses there until they could no longer sustain it.

The shopping center briefly left family hands, but it fell into disrepair under a new owner, who later lost it to foreclosure. Grandson LeRoy Gibbs II and his wife, Tracy, repurchased the center in 2015 and revived it as the Gibbs Next Generation Center. The hope is that the following generation — including LeRoy “Tripp” Gibbs III, now 12 — will carry it on.

LeRoy II credits his grandmother, who not only built wealth and passed it on, but also showed succeeding generations how it was done. It was a lesson that few descendants of the victims of the race massacre had an opportunity to learn.

“The perseverance of it is what she tried to pass on to me,” said LeRoy Gibbs II. “We were fortunate that we had Ernestine and LeRoy. … They built their business.”

___

Morrison is a member of the AP’s Race and Ethnicity team. Follow him on Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/aaronlmorrison.