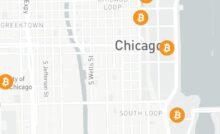

BY SANDRA GUY

As National Engineers Week draws to a close, two young women engineers say they’re excited to work on advancements in heart technologies.

Beatrice E. Ncho

Shelly Singh-Gryzbon

.

Beatrice E. Ncho, a fourth-year chemical engineering PhD candidate at Georgia Tech, focuses on engineering prototypes of transcatheter aortic valves that have a reduced risk of thrombosis (from a fluid mechanics standpoint).

She is starting her fourth year working in Dr. Ajit Yoganathan’s Cardiovascular Fluids Mechanics Laboratory.

Yoganathan has led the testing of every prosthetic heart valve design on the U.S. market for safety and effectiveness.

His lab has served as a valve approval site for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for four decades, according to a Georgia Tech research story (https://rh.gatech.edu/features/king-hearts).

Ncho, 25, has helped in testing and developing new heart valve devices.

“The heart valves in our bodies work — open and close — to allow blood flow in the right direction. When these valves don’t work properly, our blood flow is compromised,” Ncho said. “The solution to this problem is generally a replacement or repair of our heart valves with an engineered device. Sometimes, this engineered device has complications, and the patient is at risk of further problems.

“My work is to look at existing devices and test them to understand reasons for certain failures (for example thrombosis/ “blood clots” on an engineered heart valve), and then develop and test new devices that will reduce the risk of such failure,” she said.

Ncho credits her engineering training for enabling her to think critically, be analytical and seek creative solutions.

Ncho, who grew up in Bamenda, Cameroon, in West Africa, credits her family for encouraging her and her five sisters to aim for the highest in their chosen profession.

“Growing up, my father was a businessman with an entrepreneurial spirit, and my mother a middle and high school history teacher. They constantly instilled in my siblings and me the values of hard work, a great education and a valuable profession – one that contributes to the world around us,” she said.

“In an African society that mostly valued and prioritized the education and success of the male child, my parents taught us we were equally as good and all we needed to do was be hard working for whatever we wanted,” Ncho said. “My father encouraged us to pursue medicine related professions (i.e pharmacy and medicine), but I always wanted to be an engineer.

“I thought it was an exciting profession — one where you think of an idea and bring it to reality. I told my father that my compromise with him was I will pursue a profession that allows me to be an engineer that addressed medicine related problems.”

Ncho now encourages girls and young women to pursue engineering.

“My main advice for people I mentor is to have a vision and a why — a reason,” she said. “You may not have everything figured out, but have a rough idea of where you’re headed. Be also open to detours and changes along the way. The journey will be challenging, but never forget your reason for doing it because it will encourage you to stay the course.”

Ncho stays motivated by making “Determination, Discipline and Dedication” a personal motto, and remembering that whatever she does “is in service of others and bigger than me.”

She chose chemical engineering because of its near-limitless career possibilities, including work with oil and gasoline, energy, plastics, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and medical devices.

Ncho earned her bachelor’s in Chemical Engineering (Summa Cum Laude) from Texas Tech University in 2016, and her master’s in Chemical Engineering from Georgia Tech in 2018. She is expected to graduate with a Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering, and a minor in Biomedical Engineering, in December 2020.

She intends to join the medical device industry after graduation, working as a Research and Development engineer who uses engineering fundamentals to continue to provide solutions to medical-device issues.

Shelly Singh-Gryzbon, PhD, a former post-doctoral fellow in Yoganathan’s lab, focuses on developing models of heart valves on the computer.

These models can be used to understand how heart diseases develop or progress; to help design treatments or devices for the heart diseases, or to perform virtual surgery to help doctors decide the best procedure/device to use on a patient.

“As an engineer, you learn how to take highly complex, real-life situations and understand them using fundamental laws of physics,” said Singh-Gryzbon, 32, who is now a lecturer in the Department of Chemical and Process Engineering at the University of the West Indies in Trinidad and Tobago.

Singh-Gryzbon grew up in Arima — a small town in Trinidad – and she credits her parents and teachers at her semi-private all-girls school for encouraging her to pursue her dreams and her favorite subjects, which were always math and science.

“The school and the teachers played a huge role in my upbringing, and truly pride themselves on developing strong, independent and confident women,” she said. “My mom and dad never restricted us from any activities because we were girls.”

Singh-Gryzbon earned her bachelor’s degree in chemical and process engineering from The University of the West Indies; her master’s in chemical engineering from Imperial College London, and her PhD in chemical engineering from Imperial College London.

She said she now hopes to use her training and experience to spread awareness of the role engineers can play in medicine and medical technology in Trinidad and Tobago, and set up a program that fosters collaboration and communication across the medical, engineering and natural science disciplines.

Filed under:

Uncategorized